Early June 2023, Filadelfia, Chaco Province, Paraguay.

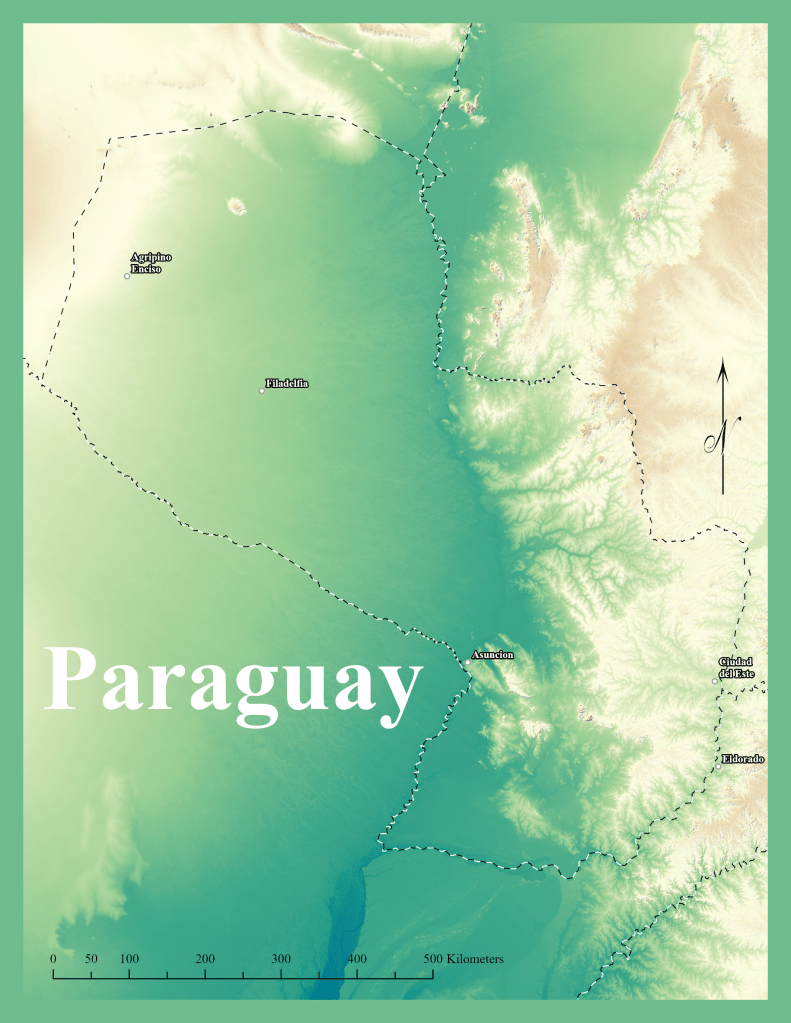

After I bade farewell to Mbaracayú, I headed west. The country of Paraguay can be divided into two essential bio regions: the *former* Atlantic Forest in the east and the Chaco in the west. This very basic false-color elevation map of Paraguay that I made before leaving shows how the two regions have very different landscape textures, and a very stark north-south boundary that is the Paraguay River:

The forested east has rolling hills and a pretty strong river network, and receives quite a bit more rainfall. The Chaco is flat and dry, a massive sedimentary plain sloping down from the foothills of the Andes in Bolivia, made up of 5 immense alluvial fans. I would guess that it was never rained on enough to allow deep valleys to form, and a very limited ‘base level’ meant any rivers just meandered and then dried up without carving canyons, leaving meandering river-shaped grasslands that you can still see on Google maps.

The last real bustling metropolis of the Paraguayan Chaco is a German-Mennonite-founded town called Filadelfia. The bus there left Asunción at 11pm, and if there had been light I would have seen the landscape change from hilly farms to flat ranches. There was no light, but it didn’t matter since I was able to sleep on this bus. When the AC finally kicked on it was very cold, and the guy next to me had a warm blanket… I was just kicking myself for leaving my puffy jacket in my bag when to my amazement he tersely elbowed me and offered me a corner! I nearly got a lump in my throat as I accepted the this Gaucho’s fuzzy pink sign of kindness. The bus headed west.

We arrived at about 4:30am, and after thanking my friend stepped off the bus into the big city of Phil—sorry—Filadelfia. The bus station was the smallest I’d seen, a single ticket window and a few very tired people sitting on large sacks or cardboard boxes of unspecified contents, the likes of which will be familiar to anyone that frequents Latin American buses.

Someone I’d been in touch with had suggested I find the Hotel Florida and get breakfast there, since they served a proper German breakfast starting very early. I found the Hotel Florida, and after blearily trying to explain what was going on to the concierge he shrugged and gestured towards the breakfast buffet which cost about $2. It was actually a pretty great spread, but that is beside the point.

After filling up on sausage, pfannkuchen, eggs and 3 cups of espresso I set off walking out of town at about 5:30. I had been recommended to go to a place called Estancia Iparoma (The Sweet-Air Ranch) and apparently it was easy to hitchhike. After walking for a few big blocks I saw this comical sign:

The pavement did end as promised, and once I figured out which road led the way I was headed, I stuck my thumb out. After about two minutes, the second pickup truck that passed skidded to a halt… my jaw dropped! How lucky was I. The driver knew where the ranch was and dropped me off at the gates, where I walked the 1km driveway right at sunrise, greeted by a roosting flock of several hundred Monk Parakeets, some distant Buff-necked Ibis and a few dozen White-browed Meadowlarks (whose bills are too stubby to be called meadowlarks if you ask me. A pair of Turquoise-fronted Parrots flew over me, and I was reminded of just how pretty Amazona parrots can be; I’d heard these birds many days at Mbaracayú but never seen them.

At the ranch house I dropped my backpacks off in the room, and walked around on the property for a bit. I hadn’t visited the Chaco before and so it was exciting to visit a new place with a whole new set of birds. The Rufous Hornero, so numerous in most of Argentina and eastern Paraguay, is here replaced with the extremely cute Crested Hornero, a slightly smaller species with a gnome-like pointy crest. Several White Monjitas kept watch from exposed perches around the yard, and a pair of Burrowing Owls sat over their burrow in an empty corral. Four smartly-colored Ringed Teal, a bird that I’d often noticed in the waterfowl section of the Merlin App, eyed me cautiously from a small pond, and a bizzare Whistling Heron whistled as it flew past.

I was most excited to see a very cool White-fronted Woodpecker (which could be called cactus woodpecker based on its nesting habits) and the attractive Greater Wagtail-Tyrant, both of which were lifers.

The Chaco itself is a unique thorn-scrub habitat that covers the eastern bit of Bolivia, the western bit of Paraguay and a big part of north-central Argentina. It’s a dry, flat (as illustrated in the map above), and very sparsely-populated region, similar in that way to Patagonia, also similar in that the overwhelming majority of the land is owned by a small minority of the people. The ranch I was staying at was a tiny 600 Hectares, one of the smaller properties around. On this ranch there were several areas of natural Chaco forest, with tracks that allowed humans to pass. Seeing the habitat up close was fascinating. Massive 5-meter cacti punctuated a brushy forest so dense it literally could not have been walked through. I think this is a contender for the most-difficult habitat for humans to navigate; I stayed on trails the entire time. The extremely cute rabbit-like Maras had no trouble navigating the brush.

There are a few national parks across the Chaco (two in Paraguay) and the cheap land means they’re relatively large. So in some senses the Chaco is well-protected, since it seems likely that many species could exist within these parks alone. But from the bird’s eye view (and the opinion of several biologists I spoke with at the Moises Bertoni Foundation) it is also teetering on the edge of a pretty sweeping destruction. If you look at the area north of Filadelfia on Google Satellite View, it becomes clear what the issue is: the natural Chaco forest appears as dark squares outlined by white roads and checkered with yellowish fields. Upon zooming out it’s easier to see the ‘stronghold’ of dark, uncut scrub-forest a bit further from the population center of Filadelfia. But if you zoom in to those areas, little white roads appear.

Those roads mostly didn’t exist a few years ago. And a few years from now, quite a lot of that lovely, dark, thorny forest that covers so makes the region unique is sure to be munched up by machines arriving via those roads.

The recent development of Filadelfia has led to a massive influx of ranchers, mostly German and Ukrainian immigrants (sometimes second or third generation), who are very successfully slicing up a wonderfully unproductive and wild part of Paraguay and making it dreadfully productive. Many Paraguayans have moved to the region, but relatively few are landowners; most work on immigrant-owned ranches. It’s a pretty remarkable situation.

I thumbed another ride from a third-generation Ukrainian who lived in the south of the country, but works in the Chaco as a cropland engineer. He was a tremendously nice guy, going a few miles out of his way to drop me off and enthusiastically saying how excited he was that I was visiting and learning about this wonderful area. When he started excitedly talking about how the Chaco might reach one million hectares of cropland any year now, I just had to smile and congratulate him on his good business. It’s an area of rapid development, which will come at a cost to habitat connectivity, acutely affecting populations of large mammals, like Jaguars and Maned Wolves.

I had plans to visit Parque Nacional Teniente Agripino Enciso, but my stomach canceled on me, catching one of the nastier bugs I’ve had this year. I am convinced that I’ve just had bad luck and it’s not a weak stomach; every time I’ve gotten sick others came down with the same thing after eating a meal. Oh well. I stayed at Iparoma for a few days, riding out the symptoms while staying sprinting-distance from the toilet. This proved to be a surprisingly rewarding spot, with some incredible species like Black-bodied Woodpecker (endangered, sought-after Chaco endemic), Chaco Owl, Great Rufous Woodcreeper, Spot-backed Puffbird, Red-Crested Finch, Scimitar-billed Woodcreeper and Lark-like Brushrunner all within a 3-minute walk from my room.

I heard one funny song which I thought originally was a quiet Antshrike in the bush next to me, but then realized it was a much farther, louder noise, definitely one of the two species of crane-like Seriema that can be seen here. After listening to recordings of the two species I decided that it sounded much more like the rarer, sought-after Black-legged Seriema, which would have been a lifer. But some birder ethics in my soul said that misidentifying it so egregiously meant I could NOT add it to my list. I never heard it again, and so it’ll have to wait until I can next visit the Chaco.

I also had a nice surprise when I heard a British accent coming from a tour group that visited one evening. I stopped eating dinner to go out and say hello, and it my suspicion was correct, it was Paul Smith, the original Paraguay contact that Adam Betuel connected me with last year! Paul was the one who first recommended that I reach out to Moises Bertoni, so it was really great to get to thank him in person. Amazingly enough he was wearing a Georgia Audubon t-shirt!

I also visited a pretty cool museum in Filadelfia, which had an excellent collection of taxidermied birds and other animals. That evening I tried a “Filadelfia Steak Sandwich” which clearly was trying to be a cheesesteak but was not much like one at all.

Instead of taking the long bus back from Asunción to Buenos Aires, I had decided earlier in May that it would be worth spending the extra $40 to get the plane ticket, and save about 18 hours of uncomfortable time in a seat. I hope the Watson Foundation is okay with that decision. I thankfully had recovered from my stomach bug by the time I caught the bus back to Asunción for the flight, and soon arrived back for my last visit to Buenos Aires before leaving Latin America. The city has honestly grown on me quite a bit; as I write this I’m in Indonesia and I really do miss the crappy espresso, trendy cocktail bars and cheap but filling European-style food. I may never eat quite so much steak again in my life (probably for the best) but it sure was fun to dive into the culture of such an interesting and distinctive region.

I’m finally catching up on my blogs; I’m writing this from a small island called Siau north of the larger island of Sulawesi. Some birders will instantly know what species I was dreaming of when I decided to visit Siau, and others will have to wait for that blog to come out.

Year List: 686 | Lifers this year: 419 | Life List: 1705

Leave a comment